Wilco’s Jeff Tweedy talks about how he and his band put together one of the best albums of the year. By Allan Martin Kemler

08/08/2002

Nothing ventured, nothing gained goes the cliché, and it’s true. There is a direct correlation between how much a person is willing to fail and how much they can possibly achieve.

But on the other side of the coin lies the possibility for total destruction. So how can a person tell whether they are embarking on an exhilarating flight of fancy that will catapult them to a new level of success or simply diving headlong into an abyss? Perhaps there is no correct answer. Maybe each of us just has to discern what success is worth and then balance it with a commensurate level of risk.

Whatever the answer, Jeff Tweedy, courageous hero and vanquisher of major-label foes, not to mention front man and brain trust for Chicago’s alt.this-n-that rockers, Wilco, has found success, and it has come hand in hand with major risks.

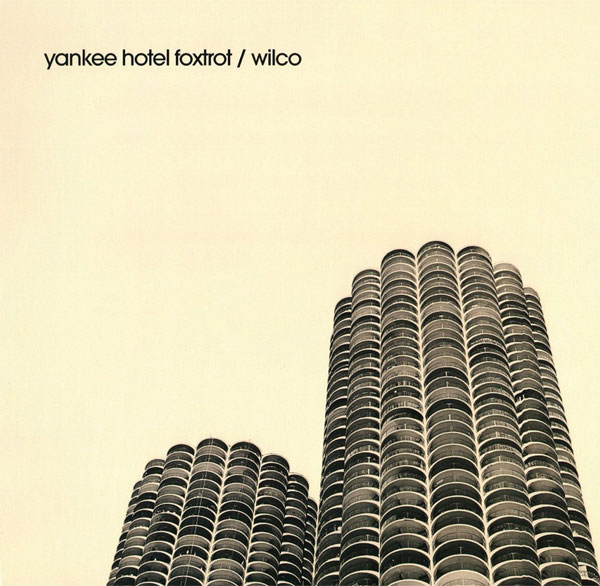

Following up 1999’s ambitious Summerteeth with an even more ambitious record his former record company (Reprise) ultimately didn’t want, Tweedy split from longtime collaborator and friend Jay Bennnett and original drummer Ken Coomer mid-way through the recording of Yankee Hotel Foxtrot (Nonesuch) amidst creative differences.

Next, the former Uncle Tupelo member tinkered with good fortune by venturing even farther afield from the roots rock sound that was formerly his calling card and topped it all off by snarkily announcing in the Chicago Sun-Times that Ryan Adams could have his band’s old sound. Dangerous moves, all.

But it’s a curious thing, what makes one man cower and another man thrive. And curiouser still trying to explain it. Nevertheless, on the new album’s fourth track, “War on War,” Tweedy gives listeners insight into his thought process, when he sings “You’ve got to lose/You have to learn how to die/If you wanna be alive” Tough talk to walk, Tweedy acknowledges, but the alternative is none too pleasant either.

“I think somehow you need to get to a certain point in your life where the notion of failure is absurd,” explained Tweedy regarding his lyrics and personal philosophy from his home in the Chicagoland area. “I feel like doing this [making music], and if I don’t do it I won’t feel as good as when I am doing it. Really, what’s the worst that can happen? You play the worst rock ‘n’ roll show ever played?”

As if anyone could. But don’t be mistaken. This is not merely the pretentious rambling of some dilettante jackass, but rather the honest opinion of a man who has been involved in more than a decade’s worth of artistic success. Who better to judge what it takes to be artistically successful and personally fulfilled?

Yankee Foxtrot Hotel, for the uninitiated, is a fantastic record. It unfolds like the dog-eared chapters of an old novel, with each song working back and forth against the psychic terrain of the record’s exposition, foreshadowing climaxes and hinting at greater truths. In stark opposition to many of today’s popular records, it doesn’t sound like two singles surrounded by a bunch of filler. Neither does it sound like some sprawling ode to Brian Wilson aching to tinkle a few sleigh bells.

More remarkable still, is the fact that Tweedy said that the version currently sitting on record store shelves is just one of several possible versions that lay between the faders prior to avant-composer Jim O’Rourke’s work during the mixing process.

“I think Jim made an enormous contribution to the record,” lauded Tweedy, “and I don’t think it’d be what it is without Jim’s involvement. We were excited about our record. We were happy with the material and we felt confident that we could make a good record mixing it ourselves or with any number of people. But at the same time, I think the best record that was there is what we excavated through our collaboration with Jim.”

When asked how he viewed his contribution to the record, the itinerant O’Rourke said he simply tried to find what each song “was” and then let that feeling guide him. Where necessary, additional piano or percussion parts were recorded to strengthen songs, but always with an eye toward how they would affect the record as a whole, he said.

“Many people who have never worked on a record or been privy to how they’re done, don’t usually know how much a mix can radically change what a song is,” contended O’Rourke. “We had quite a few possibilities with each song once we decided how to approach them. For example, in “Hot in The Poor Places” we radically restructured the song and rerecorded the opening piano part many times using a coil mounted to a magnet bolted on a neck to resonate a guitar tuned to the same chords as the piano. So the end result was just the resonance of the chords, because we felt any instrumental attack that early in the song would be distracting to the next section.” Technical innovations, however, were not the only unique factors guiding the album’s creative arc. Influenced by such experimental and surrealist authors as Italo Calvino, Gertrude Stein and André Breton, Tweedy said he filled notebooks with free-writing and, then, once he’d forgotten what it was he wrote, usually months later, he would edit the books into poems. From the poems, he said, he took individual lines, which then eventually became songs.

“In a lot of cases I’d have a lyric that just became really linear or came across as a very story-based song,” Tweedy explained. “Then I’d start taking lyrics away and see how the story changed or if it stayed the same. I like to edit until I feel like it’s good the first time we perform it in the studio. Then I try to sing the songs without looking at the lyrics, and if I forget them I’ll free-style. I just try to get inside the song and imagine what comes next.”

A grand as Yankee Foxtrot Hotel is, there were a number of excellent songs that didn’t make the cut. Adhering to a sort of internal logic to decide, Tweedy said that any song that was intrinsically important to the record which didn’t fit the sonic criteria was worked on diligently until it did. Any song that didn’t find its way onto the album, he said, was left off because there was either another song that represented the same idea, it was “goofy” or because it was just plain sombre. “There’s a couple of songs that I think we’re all happy aren’t on there,” he admitted.

Live, the band doesn’t seem to be having any problem listeners might expect fleshing out the everything-but-the-kitchen-sink sound they recorded in the studio. In fact, Tweedy reported that he feels they’re doing a better job than ever of not just presenting the band’s last two records, but also putting more effort into performing the older material. Everything sounds truer, he said. Likewise, he also noted that he’s found it to be rewarding to put the time in to learn the more recent albums’ arrangements and to figure out how to present as many of their textures as possible as a four-piece.

Nevertheless, it all comes back to risk. The success of the music Tweedy and his mates have made and the pleasure others derive from it bears an inverse relationship to their collective desire to please themselves—and in that equation success is not always a foregone conclusion. But as for how he arrived at that noble position between self-indulgence and artistic restraint, Tweedy replied, “Maybe it’s not your job to know if you suck or not.”

Allan Martin Kemler for Crud Magazine© 2002